Murder Mystery

Baz’s Christmas Soirée

Kruger Park Hostel

Welcome to the Murder Mystery I created for our guests at Christmas Dinner

in 2025! We had an incredible time—full of fun, intrigue, and even a few

history lessons. This game works beautifully whether you have a small group of

8 or a lively crowd of 40, and it’s designed to be replayed as often as you

like.

I highly recommend that everyone comes dressed in costume to

really bring the story to life. A themed meal adds to the atmosphere as well.

For our event, we served finger food, but next time I’m considering starting

with a cocktail party, then sitting down for a main course, with drinks and

snacks served later so guests can mingle and discuss clues as the evening

unfolds.

Whether you’re a seasoned sleuth or a first-time detective,

I hope you enjoy the experience as much as we did

Table of Contents

Phillip

(formerly Philipp, Prince of Eulenburg) – Oliver

Labotsibeni Mdluli (Queen Regent of

Swaziland) - Truddy

Sisi

- Empress Elisabeth of Austria – Marion

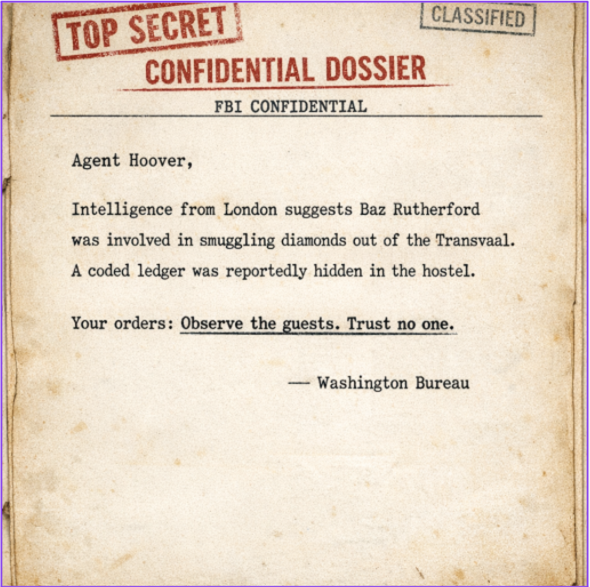

CONFIDENTIAL

– HOOVER’S BLACKMAIL DOSSIER

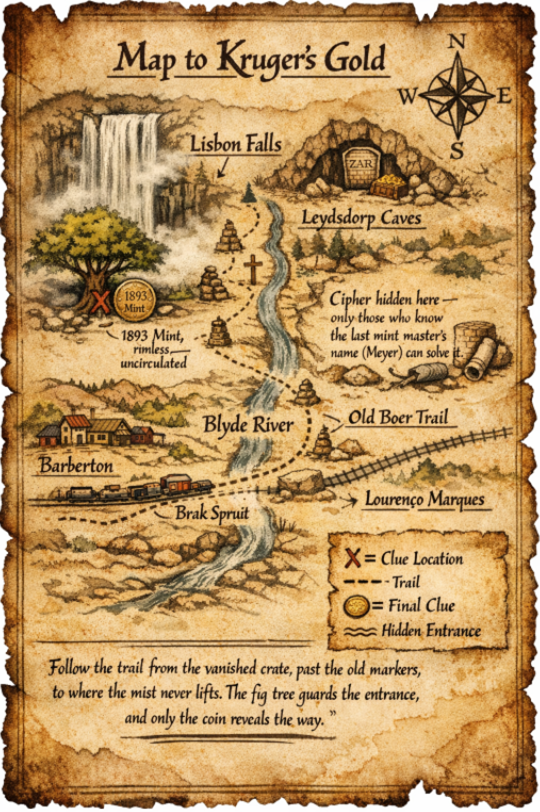

Bag

of Kruger Gold with Treasure Map

Love

Letter to Baz from Josephine

For

Marion (Sisi / Empress Elisabeth)

Zelda

Fitzgerald’s Personal Diary

Gossip

to be spread by Josephine Baker

Notes

give to Characters by Hoover

Komatipoort

Chronicle – 20th December 1912

Note

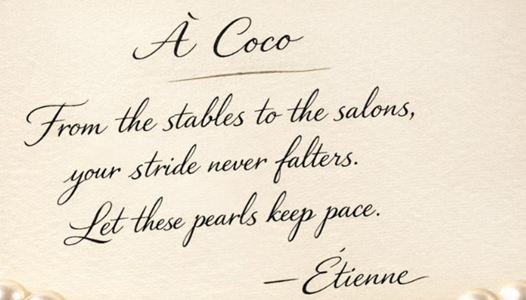

in bag of Pearls belonging to Eleanor

Letter in Chest of Gold and Dimond’s

Box of Pearls – Stolen from Coco by

Baz

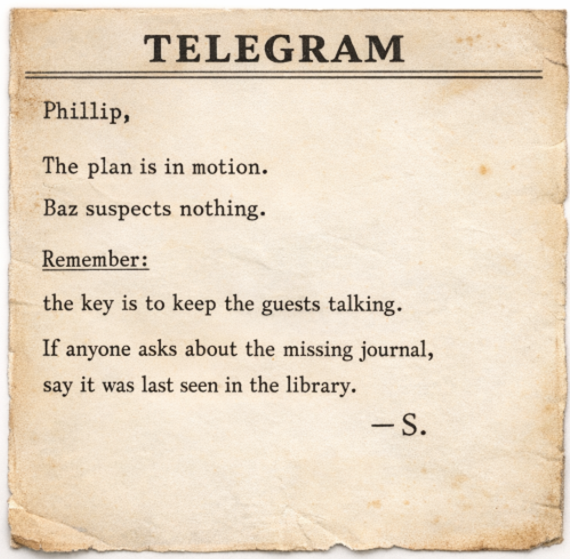

Message

sent to guests day before

First

Email to Guests to choose character

The following characters have

already been taken:

Historical

Context: December 1912 – Global Turmoil & Local Tensions

Behind

the books in the bookshelf

The

Victim and Host of the Evening - Sebastian “Baz” Rutherford

Music

Play List - 100 Greatest Songs of the 1920s

Guest

Characters

Edward, Prince of Wales

Basic

Details

- Nationality: British

- Profession: Heir Apparent (Prince of Wales, future King Edward VIII)

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 18 years old (born 1894)

- Fictional Age in Story: ~18 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Edward, Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII), is historically known for the constitutional crisis of his abdication in 1936 to marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcée – a decision that shook the British monarchy and ultimately led to his younger brother George VI taking the throne (and thus making Elizabeth II eventual queen). As Prince of Wales, Edward was popular in the 1920s for his charm and modernization of the royal image, but his reign as King was short-lived (less than a year) due to the abdication. His life symbolises the clash between personal desire and public duty. Post-abdication, he lived as the Duke of Windsor, a somewhat lamented figure. Though his direct impact as monarch was limited by the abdication, the event itself had significant historical impact, notably reinforcing the British monarchy’s commitment to duty over personal preference in the generations since. Additionally, Edward’s perceived Nazi sympathies during World War II tarnished his legacy. In sum, Edward VIII is significant for the dramatic abdication that tested and ultimately strengthened the British monarchy’s stability, and for serving as a cautionary tale of royal responsibility.

Early

Life and Background

Born in 1894 as the eldest son of the future George V, Edward (known in the family as David) enjoyed a privileged upbringing but one tightly controlled by Victorian norms. He was educated by tutors and at naval college, though he was not an academic standout. Instead, young Edward excelled in social graces and sports, developing a rakish charm. By 1911, he was invested as Prince of Wales in a grand ceremony at Caernarfon – a conscious effort by his father to prepare him as a unifying figure. In 1912 (at 18), Edward had begun military training at Osborne and Dartmouth, though he was deliberately kept from front-line action in World War I due to his position (which frustrated him). Early on, Edward showcased a warmth and informality that endeared him to the public; even as a teen prince he would slip out of palaces to mingle with ordinary people or sneak in jazz dance sessions (to the mild scandal of courtiers). Those early experiences – chafing under strict royal protocol, witnessing the pomp of empire tours with his father – shaped Edward’s restless, modern personality. He learned to present a charming front but also developed a streak of rebellion against stuffy tradition. By the end of 1912, though still in training, Edward had taken on light official duties: laying foundation stones, reviewing boy scouts, etc., experiencing the first tastes of public expectations. These formative years left him both acutely aware of his destiny and privately yearning for greater personal freedom, foreshadowing the struggle that would later define him.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Edward VIII’s legacy is defined almost entirely by his abdication. He was the first English monarch to voluntarily relinquish the crown since medieval times, and this unprecedented move rocked the British Empire. The abdication had significant historical consequences: it averted a potential constitutional crisis (had he tried to remain king while flouting Church and government opposition to his marriage) and put his stammering but dutiful brother George VI on the throne – who, with his wife Queen Elizabeth, skillfully guided Britain through World War II, arguably better than the flighty Edward might have. Thus one could argue Edward’s abdication indirectly ensured stronger wartime leadership. Culturally, Edward’s romantic choice over duty became legendary – a tale retold in films, plays and endless gossip, casting a long shadow on how the monarchy is perceived when balancing personal happiness with public role. The episode led the royal family to enforce more carefully the expectation that royals marry suitably, at least until more modern times. Outside the abdication, Edward’s legacy is mixed: his initial popularity as a globe-trotting Prince of Wales introduced a more informal, approachable style to royal engagements (he was dubbed “the people’s Prince” in the 1920s). However, his later suspected Nazi sympathies – he and Wallis were cozy with Hitler’s regime in the late 1930s – tarnished his image; had he remained king, this association might have endangered the monarchy or Britain’s integrity in WWII. In exile as Duke of Windsor, he had essentially no impact on events, living a life of leisure. Over time, historical judgment on Edward has been largely negative regarding his sense of duty, but sympathetic regarding the constrained royal marriage customs he defied. Crucially, his abdication reinforced that the monarchy must put duty above personal desire – a principle that Queen Elizabeth II, his niece, held sacrosanct for her reign. In summary, Edward VIII’s impact lies in the dramatic way he altered Britain’s royal succession and set an example (however unwittingly) that duty and stability trump individual will in the institution of the Crown.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, the young Prince Edward had few political or policy achievements – such were not expected of an 18-year-old heir – but he had begun carving out a role as a modern, compassionate royal figure. In that year he undertook his first solo public engagements and short tours around Britain. One could cite his successful investiture as Prince of Wales in July 1911 (just months prior) as an early achievement: speaking a few words in Welsh and conducting himself with poise, which earned public praise. In 1912 he toured some British industrial towns – in one notable visit to the coal mines of South Wales, he descended into a pit and spoke with miners covered in soot, a gesture almost unheard of for a royal then. This was an achievement in bridging class divides symbolically; newspapers reported positively how the Prince “showed genuine concern” for working conditions. Edward also threw himself into military training with zeal. By late 1912 he had passed his preliminary naval examinations and begun training with the Grenadier Guards; superiors noted his exemplary camaraderie with fellow cadets and his enthusiasm for soldierly duties (even if they kept him from actual combat later). Another subtle achievement: he became something of a style icon among Europe’s youth. His casual tweed suits and unstuffed manner – shaking hands with line workers during factory visits – started to loosen the stiff image of the royals. While harder to quantify, this contributed to the monarchy’s adaptation to the 20th century. Additionally, Edward at 18 was fluent in French and improving in Welsh, showing an aptitude for languages and diplomacy. Summarily, as of 1912 Edward’s “achievements” were mainly symbolic and social: successfully stepping into the public eye, connecting with diverse subjects, and – as intended by his father – beginning to embody the future of a monarchy that could engage with a changing society. These early efforts laid the groundwork for the extremely popular figure he would become in the interwar era (before his later controversies).

Motive:

Background:

In 1912, Edward is a young, restless heir to the British throne, chafing under

the constraints of royal protocol and desperate to carve out a more modern,

independent identity. He is already under intense scrutiny from his family, the

government, and the press, and any hint of scandal could have serious

consequences for his future and the monarchy’s reputation.

Baz Rutherford, a charming and well-connected adventurer,

crosses paths with Edward during a social event in London. Baz quickly

ingratiates himself with the young prince, offering him a taste of freedom and

excitement away from the stifling world of court. Baz introduces Edward to

exclusive parties, discreet jazz clubs, and a circle of bohemian

friends—including several women (and men) whose company would be considered

scandalous by royal standards.

Trusting Baz, Edward confides in him—sharing letters,

private thoughts, and even details of a secret flirtation with a young American

woman he met at a dance. Baz, ever the opportunist, quietly collects these

confidences and, when his own fortunes take a downturn, threatens to leak

Edward’s private letters and stories to the press or to political rivals unless

the prince does him a series of favours.

Edward is horrified. The exposure of his indiscretions would

not only humiliate him personally but could also bring shame on the royal

family, jeopardise his position as heir, and trigger a constitutional crisis.

Worse, Baz’s threats make Edward feel trapped and manipulated, forced to act

against his own conscience and the expectations of his family.

For Edward, Baz is not just a blackmailer—he is a direct

threat to the stability of the monarchy and to Edward’s own fragile sense of

self. The only way to protect his future, his family, and the Crown is to

ensure Baz can never reveal what he knows.

Summary:

Edward, Prince of Wales, wants Baz dead because Baz is blackmailing him with

private letters and secrets that, if revealed, could destroy his reputation,

endanger the monarchy, and ruin his chance to shape his own destiny. For

Edward, eliminating Baz is an act of desperate self-preservation and a defence

of the royal institution he is destined to lead.

In-character quote:

“He promised me freedom, but instead he shackled me with my own secrets. For

the sake of my family—and my future—he must be silenced.”

Sol Plaatje

Basic

Details

- Nationality: South African (Setswana heritage)

- Profession: Journalist, Activist, Politician

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 36 years old (born 1876)

- Fictional Age in Story: 36 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Sol Plaatje is historically important as a pioneering black South African intellectual and co-founder of the African National Congress (ANC). A journalist, polyglot, and author, he was among the first to document and voice the experiences of black South Africans under colonial rule. He travelled to Britain and the USA as part of delegations to protest racial injustices (notably the 1913 Natives Land Act which dispossessed black people of land). Plaatje’s diary of the Siege of Mafeking (1899) is a vital firsthand record of the Boer War from an African perspective, and his novel Mhudi (1930) is one of the first English novels by a black African. He is celebrated as a champion of African rights, a chronicler of African life, and a visionary who laid groundwork for South Africa’s freedom struggle through the ANC.

Early

Life and Background

Born in 1876 in the Orange Free State, Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje grew up speaking Setswana, later mastering English, Dutch, German, and other languages – he worked as a court interpreter by his early twenties. This linguistic prowess opened doors: by 1902 he became editor of Koranta ea Bechuana, a Setswana-English newspaper campaigning for black rights. Plaatje’s early life was defined by the discriminatory regime of the British and Boer administrations: he saw black families pushed off their land and their political voices silenced. This spurred him to activism through the pen. By 1912, Plaatje had helped form the South African Native National Congress (the ANC’s original name) in Bloemfontein, where he was elected its first Secretary-General – a major achievement marking the formal start of black political organisation in South Africa. He was also a keen cultural preserver; in 1912 he began translating Shakespeare into Tswana to prove African languages’ capability for high literature. These experiences – witnessing oppression, leading a new political movement, and striving to bridge African and European cultures – cemented Plaatje’s role as a voice for his people at a time when such voices were systematically stifled.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Sol Plaatje’s legacy lies in being a trailblazer for African journalism, literature, and political activism. As one of the first black newspaper editors and war correspondents in South Africa, he provided a perspective that had been missing from the public record. His detailed diary of the Mafeking Siege corrected biases in colonial accounts and stands as a crucial historical document. Co-founding the ANC in 1912, Plaatje set in motion the organisation that would eventually achieve majority rule in 1994 – an indisputable impact on South African history. Though he died in 1932, before seeing major victories, Plaatje’s relentless lobbying abroad (he and others went to London in 1914 to petition against the Natives Land Act) laid early groundwork for internationalising South Africa’s racial injustices – a strategy the anti-apartheid movement would later intensify at the UN. Culturally, Plaatje’s novel Mhudi broke ground as an African historical romance told from an African viewpoint; while published posthumously, it’s now lauded as a classic and studied in schools, cementing his status as a founding figure in South African literature. He also compiled Setswana proverbs and folktales, preserving indigenous knowledge for future generations. In a broader sense, Plaatje’s life – straddling eras of colonialism and resistance – symbolizes the early intellectual resistance that blossomed into full-fledged liberation movements. Towns, university buildings, and an annual lecture series in South Africa bear his name, ensuring his contributions to language, journalism, and freedom are remembered. The ANC’s continued existence and success owe something to Plaatje’s organisational groundwork and advocacy – making him a revered figure as one of the fathers of South African democracy.

Achievements

as per 1912

By 1912, Sol Plaatje had already notched several landmark achievements against formidable odds. That year, he played a key role in the founding of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the country’s first national black political organisation. At the SANNC’s inaugural conference in January 1912, Plaatje was appointed Secretary-General – a signal honour reflecting his eloquence and organisational talent (he drafted much of the Congress’s constitution and early correspondence). Prior to that, Plaatje had made his mark as a pioneering editor: from 1902 to 1908 he edited Koranta ea Bechuana, becoming one of the first black South Africans to run a newspaper (printing in both Tswana and English). By 1912, he launched another newspaper, Tsala ea Batho (“The Friend of the People”), in Kimberley, using it to speak out against the oppressive new land segregation laws. Another crowning achievement was his work as a translator and intellectual bridge: in 1911 Plaatje finished translating Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors into Tswana – an extraordinary scholarly feat demonstrating African linguistic prowess. He even performed scenes with an African cast, to the astonishment of white audiences. Additionally, Plaatje had earned respect as a wartime hero of sorts: in 1900 during the Siege of Mafeking, he served as a court interpreter and kept a diary throughout, recording the bravery and suffering of African residents. By 1912 he had polished this diary into a manuscript (though it wouldn’t be published until much later, it was already an enormous personal achievement and historical record). Summed up, Plaatje by 1912 was a journalistic trailblazer, a community leader, and a cultural innovator – he had co-founded the vehicle for African political aspirations (SANNC/ANC), fearlessly run newspapers advocating black rights, and shown that African voices could command literary authority. These accomplishments heralded the greater role he would continue to play in South Africa’s journey.

Aleister Crowley

Basic

Details

- Nationality: British

- Profession: Occultist, Ceremonial Magician, Poet

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 37 years old (born 1875)

- Fictional Age in Story: 37 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Aleister Crowley is historically significant as one of the most famous (and infamous) occultists and mystics of the early 20th century. Styling himself as “The Great Beast 666,” Crowley developed the religion of Thelema, which declared “Do what thou wilt” as the whole of its law, and he practiced elaborate magical rituals. He wrote extensively on magic, yoga, and esoteric philosophy (e.g., The Book of the Law in 1904 is a central text). Crowley’s rejection of conventional morality and embrace of sexual and drug-related experimentation earned him a scandalous reputation in his day – he was dubbed “the wickedest man in the world” by the tabloids. Despite his notoriety, Crowley’s impact is seen in the modern occult revival; he influenced Wicca, Satanism, and the New Age movement, and his ideas on personal spiritual freedom presaged the counterculture of the 1960s. In pop culture, he remains an iconic figure of dark magic and eccentric excess.

Early

Life and Background

Born in 1875 to a wealthy, devoutly religious family (Plymouth Brethren) in England, Edward Alexander Crowley rebelled fiercely against his strict Christian upbringing. Expelled from Cambridge, he immersed himself in the occult. By his twenties he joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a secret society of magicians, where he studied under luminaries like S.L. Mathers. Crowley, however, quarrelled with many in the Order (notably W.B. Yeats) and left to pursue his own path. A natural polymath, Crowley travelled the world – climbing mountains (he led one of the first expeditions on K2 in 1902), studying yoga in India, and absorbing Eastern philosophies. In 1904, during a stay in Cairo with his wife Rose, Crowley experienced what he claimed was a revelation from a spirit named Aiwass who dictated to him The Book of the Law. This event marked the birth of Thelema and Crowley’s self-realisation as a prophet. By 1912, Crowley had joined and quickly risen in another occult order, the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), bringing with him his Thelemic sexual magic practices. He had also scandalised polite society with publications of erotic poetry and accounts of magical rites. Thus the Crowley of 1912 was a man in full pursuit of occult mastery, having founded his own Abbey of Thelema in Sicily (slightly later, in 1920) and already infamous for his libertine lifestyle and magical exploits. Early influences like Golden Dawn ceremonial magic, eastern mysticism, and personal idiosyncrasy combined to shape the self-styled “Magus” that he was by this time.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Crowley’s legacy is highly paradoxical but undeniably influential in the realms of esotericism, literature, and counterculture. He took the Western esoteric tradition (alchemy, Tarot, Kabbalah) and updated it for modern practitioners, effectively being a pioneer of the 20th century occult revival. Orders and magical systems he touched – like O.T.O. and Golden Dawn spinoffs – continued and flourished after him, spreading concepts like the Hermetic Qabalah widely. He inspired countless later occultists; figures such as Gerald Gardner (founder of Wicca) borrowed from Crowley’s rituals, and even Anton LaVey’s Satanism took cues from Crowley’s anti-establishment stance. In literature and popular media, Crowley appears as the archetype of the dark magician – characters from Somerset Maugham’s The Magician (a thinly veiled Crowley) to modern films draw on his persona. Perhaps ironically, Crowley also influenced the arts: he was admired by avant-garde artists and later by 1960s rock musicians (the Beatles put his face on Sgt. Pepper’s album cover, Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page was an avid follower). Crowley’s “Do what thou wilt” ethos anticipated the sexual revolution and the hippie mantra of pursuing one’s true will or path. However, his legacy is also cautionary: his personal life, riddled with excess and drug addiction, showed the potential perils of unbridled hedonism – some link his deteriorating state later in life as a lesson in overindulgence. Nonetheless, Crowley’s emphasis on personal spiritual experience and freedom from conventional morality has permeated modern spirituality. Terms he coined (like “magick” with a k) and rituals he devised are standard in occult practice today. In summation, though often vilified in his time, Crowley’s impact lies in shaping contemporary occult thought, inspiring the mystical counterculture, and iconically representing the figure of the rebel mystic who sought enlightenment in the shadows.

Achievements

as per 1912

By 1912, Aleister Crowley had not yet achieved the height of his notoriety, but he already had significant accomplishments in the occult and literary arenas. He had published several volumes of poetry and mystic writings, albeit to mixed reception – notably Konx Om Pax (1907) and The World’s Tragedy (1910) – establishing him in bohemian circles as an unconventional voice. In terms of occult achievements, Crowley had performed a series of advanced magical operations: for instance, in 1909 he and his protégé Victor Neuburg conducted the much-storied “Desert Workings” in Algeria, where they evoked various spirits across the Enochian aethyrs (spheres of consciousness) – a feat chronicled in his publication The Vision and the Voice. This was an achievement in pushing the boundaries of Golden Dawn magic into new territory. By 1912 he had also climbed several major mountains (literally an early achievement): he made a pioneering (though ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to summit K2 in 1902 and reached high on Kanchenjunga in 1905, earning respect in mountaineering logs. In the realm of secret societies, 1912 marked a peak achievement: Crowley was initiated into the O.T.O. and within that year was granted leadership of its British branch. He also was busy establishing his own mystical order, the A∴A∴ (Argentum Astrum), which he founded in 1907 – by 1912 it had attracted a number of students, spreading his Thelemic teachings quietly. Additionally, Crowley had by this time formulated and published the basic tenets of Thelema: The Book of the Law was written in 1904 (though only privately circulated initially), and he had begun promoting “Do what thou wilt” among disciples. So, by end of 1912, Crowley’s achievements included significant occult publications, bold magical experiments, leadership roles in esoteric orders, and even physical feats of exploration – all contributing to his growing legend as a master of mysteries, poised to make an even bigger splash (for better or worse) in the years soon to come.

Benito Mussolini

Basic

Details

- Nationality: Italian

- Profession: Socialist Agitator (later Fascist Dictator)

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 29 years old (born 1883)

- Fictional Age in Story: 29 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Benito Mussolini is historically known as the founder of Fascism and the dictator of Italy from 1922 to 1943. He established the first fascist regime, inspiring similar movements in Europe including Nazi Germany. Under the title “Il Duce” (The Leader), Mussolini turned Italy into a one-party totalitarian state, embarked on aggressive expansion (e.g., invading Ethiopia in 1935), and allied with Hitler in World War II. His rule is synonymous with ultranationalism, suppression of dissent, and cult of personality. Mussolini’s impact is significant both as a cautionary tale of how democracies can fall to demagogues, and as a key Axis leader whose ambitions and subsequent downfall in WWII shaped mid-20th-century geopolitics. He is a central figure in the study of authoritarianism, exemplifying the transition from socialism in youth to forging a new far-right ideology that would plunge the world into conflict.

Early

Life and Background

Born in 1883 in a small town in Romagna, Italy, Mussolini was named after leftist figures (Benito after Benito Juárez) and raised by a socialist blacksmith father and devout Catholic schoolteacher mother. Fiery and intelligent, young Benito was nevertheless unruly – he was expelled from several schools for bullying and defiance. He qualified as a schoolmaster but soon gravitated to journalism and socialist activism. By his twenties, Mussolini had become a prominent socialist orator and editor in northern Italy. In 1912 (at age 29), he reached a high point in his early career: he was appointed editor of Avanti! (Forward!), the official newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party. With his forceful writing and charisma, Mussolini used Avanti!’s pages to advocate strikes and class revolution, gaining nationwide notoriety. He championed radical socialist causes, opposing Italy’s imperial war in Libya (1911) and agitating for workers’ rights. These experiences in 1912 – leading mass strikes in Forlì, rousing peasants with fiery speeches – honed his skills in propaganda and crowd manipulation. Ironically, the very talents that made him a socialist hero in 1912 (magnetic leadership and bold rhetoric) would later underpin his creation of fascism. But at this point, Mussolini’s background was of a red-shirted revolutionary steeped in Marxist theory and class struggle, forging a name as one of Italy’s most formidable young socialists, even as latent tendencies of authoritarianism and ultra-nationalism stirred beneath the red banner.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Mussolini’s legacy is predominantly marked by the creation of the first fascist state – he showed the world a new form of dictatorship that rejected liberal democracy and communism in favour of aggressive nationalism and corporatism. He centralized power in Italy, crushed political opposition, and indoctrinated the populace with militaristic and extreme patriotic fervour. This had a profound historical impact: Mussolini’s Italy served as a template and ally for Hitler’s Germany, directly contributing to the outbreak of World War II and the atrocities that followed. Domestically, his regime undertook grand infrastructure projects (draining marshes, building roads) and initially restored order and pride for some Italians after a period of turmoil – achievements later overshadowed by war destruction and oppression. Culturally, Mussolini’s bombastic style and the Fascist salute became global symbols of tyranny. His downfall – executed by Italian partisans in 1945, his body hung ignominiously in Milan – was a dramatic end that has since served as the fate of a cautionary figure. Post-war, Italy swung to democracy, and Mussolini’s name became a byword for brutal dictatorship; yet, his impact lingered as neo-fascist movements claimed inspiration from “Il Duce” in subsequent decades. Internationally, Mussolini’s fascism influenced regimes from Franco’s Spain to various authoritarian governments that mimicked aspects of his rule. In historical scholarship and collective memory, Mussolini is often studied alongside Hitler and Stalin as part of the triad of interwar totalitarians – he is remembered both for his early role in destabilising the European order and for the ideology of fascism that, once unleashed, had global and devastating consequences.

Achievements

as per 1912

In 1912, Benito Mussolini was at the height of his career as a socialist leader – a paradoxical success given his later infamy. That year he secured a significant achievement: at the Italian Socialist Party congress in Reggio Emilia, he so impressively made the case for revolutionary socialism that he won election to the Party’s Executive Committee and, most notably, was appointed editor-in-chief of Avanti!, the influential socialist daily. Under his editorship, newspaper circulation soared as he made its content more fiery and provocative, galvanising Italy’s left. He also led successful general strikes in the Romagna region – for example, a 48-hour stoppage in Forlì that forced employers to reinstate fired workers and raise wages. Such outcomes made him a hero to labourers. Additionally, Mussolini in 1912 helped expel the party’s right-wing faction, asserting the dominance of Marxist maximalists; this internal discipline was an achievement in consolidating the Socialists under a radical program. As a public speaker, by 1912 he had polished a style of incendiary oratory that could hold crowds of thousands spellbound – his speech urging Italians to resist the Libyan War (1911–12) was so stirring that it prevented some regiments from embarking, an anti-war feat praised in socialist circles. These accomplishments – a top party post, editorial triumph, strike victories, and magnetic speeches – marked Mussolini in 1912 as one of Italy’s most formidable young Socialists. Little could his comrades predict that these very achievements (mass mobilisation, silencing moderates, media mastery) were training for an opposite purpose in future, but within the context of 1912, Benito Mussolini was seen as a rising star of the proletarian movement, an achievement he would later perversely invert.

Motive:

Background:

In 1912, Benito Mussolini was a prominent socialist agitator and the editor of Avanti!,

the official newspaper of the Italian Socialist Party. He was fiercely

anti-imperialist, opposed to Italy’s colonial war in Libya, and deeply involved

in organising strikes and protests against both the monarchy and capitalist

profiteers.

Baz Rutherford, posing as a well-connected British adventurer and “friend of the workers,” ingratiated himself with Mussolini’s socialist circle in Milan. Baz offered to help smuggle anti-war pamphlets and funds to socialist cells in southern Italy, claiming to support the cause of international socialism and the fight against imperialist wars.

However, Baz was in fact a double agent, selling information about the socialist underground to both Italian police and foreign intelligence in exchange for money and favours. His betrayal led to the arrest of several key socialist organisers, the confiscation of Avanti!’s secret printing press, and the exposure of Mussolini’s plans for a general strike against the Libyan war.

Mussolini, humiliated and enraged by the loss of trusted comrades and the setback to the socialist movement, saw Baz not only as a personal traitor but as a dangerous tool of imperialist oppression. In Mussolini’s eyes, Baz’s actions directly undermined the struggle for workers’ rights and the anti-war cause, making him an enemy of the revolution.

Summary:

Mussolini wants Baz dead because Baz’s duplicity led to the arrest of socialist

comrades, the destruction of vital underground networks, and the betrayal of

the anti-imperialist cause. For Mussolini, eliminating Baz is not just an act

of personal vengeance, but a revolutionary necessity to protect the movement

and strike a blow against those who profit from war and repression.

Ernest Hemingway

Basic

Details

- Nationality: American

- Profession: Writer (Novelist, Journalist)

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 13 years old (born 1899)

- Fictional Age in Story: ~19 (portrayed as a young aspiring writer in 1912)

Core

Significance

Ernest Hemingway is celebrated as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century, known for his distinctive spare prose and for chronicling the disillusionment of his “Lost Generation.” His novels and stories – such as The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, and The Old Man and the Sea – have become classics, defining modernist literary style with their understated intensity, stoicism, and themes of courage. Beyond literature, Hemingway’s adventurous lifestyle (from war correspondent to big-game hunter) made him a cultural icon of machismo and restless spirit. He won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954. Hemingway’s influence on narrative craft – the iceberg theory of omitting detail to strengthen impact – is immense, and generations of writers have been shaped by his clarity and force. In short, Hemingway’s importance lies in both his oeuvre of enduring works and his persona that together revolutionised American fiction and embodied the modern hero’s search for meaning.

Early

Life and Background

Born in Oak Park, Illinois in 1899, young Hemingway was raised with robust Midwestern values – his father taught him hunting and fishing, while his mother nurtured an appreciation for music and the arts. By his teens Hemingway was already passionate about writing and adventure. At school he wrote for the newspaper and excelled in English. Though in reality in 1912 he was only 13 (fictionally in our story he’s depicted about 19 to interact plausibly with others), he was precocious: devouring works of Twain, Kipling, and Tolstoy. He longed for wider experiences beyond Oak Park’s genteel confines. In 1917, he would defy his parents and join the Red Cross ambulance service in World War I (an experience that later informed A Farewell to Arms). But even by 1912 in this fictional conceit, Hemingway as a late teen might have run off to Kansas City to become a cub reporter – which he indeed did at 18 in reality, covering crime scenes and learning the terse journalistic style that shaped his fiction. Those early influences – the outdoor toughness from his father, the artistic sensitivity from his mother, and the journalistic training on the streets – combined to forge Hemingway’s unique voice: plainspoken yet poignant, brave yet deeply observant of life’s pains. In our story’s timeline he’s an aspiring young writer absorbing tales from older adventurers, keen to turn truth into art.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Hemingway’s legacy in literature is profound. He pioneered a new writing style – minimalist yet evocative – that broke from the ornate prose of the 19th century. His influence is seen in countless authors who emulate his tight dialogue and “show, don’t tell” philosophy (the famous “Hemingway style”). Thematically, his works shedding light on wartime trauma, existential ennui, and stoic grace under pressure resonated through the 20th century and remain resonant today. He gave voice to the Lost Generation’s cynicism in the 1920s, but also to timeless human struggles: love and loss in war (A Farewell to Arms), the dignity of the individual against fate (The Old Man and the Sea). Beyond the page, Hemingway’s larger-than-life persona – bullfights in Spain, safaris in Africa, deep-sea fishing in Cuba – impacted cultural notions of masculinity and adventure. He turned life into legend, entwining reportage with myth-making. Hemingway also contributed to journalism, e.g. his Spanish Civil War dispatches set a standard for literary war correspondence. Over time, he’s become a fixture in both high literature and popular culture (with his likeness in films, his name an adjective – “Hemingwayesque” – meaning starkly direct). Educational curricula worldwide include his books, ensuring new generations grapple with his ideas of bravery, morality, and economy of language. In summary, Hemingway’s historical impact is twofold: he reshaped literary craft in the 20th century and cemented the ideal of the writer-adventurer whose own life is an extension of his art, leaving an indelible mark on both literature and the image of the modern American man of letters.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, Ernest Hemingway’s tangible accomplishments were modest (given his youth), but he was already laying foundations for his future career. In reality a schoolboy then, our story imagines him around 19: perhaps just starting as a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star, which in truth he joined at 18 in 1917. Nonetheless, we can say that even by his teens he had honed a crisp writing style – Hemingway himself credited the Star’s style guide (“Use short sentences”) as crucial training. Another “achievement” by this stage was assembling a rich store of life experiences to fuel his writing. For instance, in 1912 Hemingway spent summers in Michigan’s north woods, mastering outdoor skills and observing nature keenly. Those days on Walloon Lake later inspired Nick Adams stories (like Indian Camp). It’s fair to claim that by this age he had won small school accolades: he edited his high school’s newspaper The Trapeze and published youthful writings there, receiving praise for their wit. Additionally, a formative event came in 1911 when he took a hunting trip with his father and successfully shot a deer – a rite of passage he described with literary flair in a school essay. Though minor, such experiences were achievements in confidence-building and gave him material infused with authenticity. In terms of personality, by 1912 Hemingway had crafted a persona of fearlessness and curiosity. He was the kid who would sneak into a local boxing match or be first to volunteer for a risky dare, all of which built the bold character that would draw the attention of editors and friends. In short, at this early stage Hemingway’s “achievements” were seeds of greatness: a budding mastery of concise writing, a trove of adventurous episodes translated into juvenile articles, and a reputation among peers as a promising young man with stories to tell – the precocious beginnings of a literary icon in the making.

Background:

In 1912, Ernest Hemingway was a young, ambitious writer just beginning to make

his way in the world. He was fiercely proud of his work, deeply sensitive to

betrayal, and already developing the code of honour and authenticity that would

define his later life and writing.

Baz Rutherford, posing as a literary mentor and well-connected publisher, befriended the young Hemingway in Chicago. Baz offered to introduce Hemingway’s stories to influential editors in New York and London, promising to help launch his career. Trusting Baz, Hemingway handed over a bundle of his best short stories and personal letters, believing this was his big break.

Instead, Baz vanished with Hemingway’s manuscripts. Weeks later, Hemingway discovered that one of his stories had been published under a different name in a pulp magazine, and that Baz had sold his work to several publications, pocketing the proceeds. Worse, Baz had also circulated Hemingway’s private letters, mocking his youthful ambitions and exposing personal details to the literary gossip mill.

For Hemingway, this was more than theft—it was a violation of trust, a public humiliation, and a direct attack on his identity as a writer. The betrayal left him embittered, suspicious, and determined never to be made a fool again. In Hemingway’s code, such a betrayal could only be answered with violence.

Summary:

Hemingway wants Baz dead because Baz stole his early stories, sabotaged his

literary reputation, and publicly humiliated him at a formative moment in his

life. For Hemingway, killing Baz would be an act of personal justice—a way to

reclaim his honour, protect his future, and ensure that no one else could ever

use his words or dreams against him.

In-character quote:

“He didn’t just steal my stories—he tried to steal my future. A man who does

that deserves nothing less than the sharp end of a knife.”

Leon Trotsky

Basic

Details

- Nationality: Russian (Soviet)

- Profession: Revolutionary Leader, Marxist Theorist

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 33 years old (born 1879)

- Fictional Age in Story: 33 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Leon Trotsky is a towering figure in the history of the Russian Revolution and early Soviet Union. As a key Bolshevik leader, he co-engineered the October Revolution of 1917 alongside Lenin, and later built the Red Army which won the Russian Civil War. He is historically important both as a master strategist and orator of the revolution, and as a brilliant, if ultimately outmanoeuvred, theorist of Marxism. Trotsky’s ideas of “permanent revolution” influenced leftist movements worldwide, positing that socialist revolutions must be continuous and international. Though later expelled from the Soviet Union by Stalin and eventually assassinated, Trotsky’s legacy endures as the fiery intellectual voice of early Soviet Marxism and a cautionary tale of revolution betrayed by dictatorship.

Early

Life and Background

Born Lev Davidovich Bronstein in Ukraine to a prosperous Jewish farming family, Trotsky became radicalised as a teenager. He was drawn into underground Marxist circles in Nikolayev and by his twenties was a committed revolutionary. Arrested for subversion in 1898, he endured Siberian exile where he adopted the alias “Trotsky” from a jailer’s name. Escaping Siberia in 1902 by forging papers, Trotsky joined Lenin and others in London to edit the newspaper Iskra (The Spark). A gifted writer and speaker, he quickly gained fame for his rousing denunciations of the Tsarist regime. During the 1905 Revolution, Trotsky emerged in St. Petersburg as chairman of the first Soviet (workers’ council), an extraordinary role for a 26-year-old. His leadership during the 1905 upheaval – articulating workers’ demands and organising strikes – cemented his reputation as a formidable revolutionary tactician. After 1905’s failure, Trotsky was again imprisoned and exiled, but escaped once more. By 1912, he was living in Vienna, continuing his agitation through journalism (he published the paper Pravda for a time) and acting as a unifying figure among internationalist socialists. These early experiences – prison, exile, radical journalism, and being at the forefront of 1905’s Soviet – forged Trotsky’s conviction in grassroots proletarian power and honed his skills in propaganda and organisation that would serve him in 1917.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Trotsky’s legacy is significant on multiple fronts. Militarily, he founded and led the Red Army, transforming a ragtag band of workers and peasants into a disciplined force that won the Civil War by 1921. This achievement arguably saved the Bolshevik Revolution at its most perilous hour. Intellectually, Trotsky’s writings – like The History of the Russian Revolution and Permanent Revolution – became canonical texts for Marxists dissident to Stalin’s later rule. He championed the idea that socialism had to spread globally (permanent revolution) rather than stagnate in one country, an idea that put him at odds with Stalin’s “Socialism in One Country” and inspired Trotskyist movements worldwide. His expulsion and exile in 1929 and eventual murder in 1940 (assassinated with an ice axe by a Stalinist agent in Mexico) made him a martyr-figure for anti-Stalinist communists. Trotsky’s name became synonymous with revolutionary purity and tragic downfall – he was the arch-rival written out of Soviet history by Stalin. Yet, outside the USSR, many saw him as the true heir to Lenin’s internationalist vision. His historical impact thus endures in the ideological struggles within socialism: Trotskyism remains a distinct strand of communist thought, advocating global revolution and critiquing authoritarian socialism. Moreover, in broader culture, Trotsky’s dramatic life – from fiery orator to hunted exile – has fascinated historians, yielding countless books and analyses. Although he never held power in a peaceful Soviet state, Trotsky’s contributions to making the revolution and shaping its early course are considered pivotal in the creation of the first socialist state, and his loss paved the way for the rise of Stalinist tyranny, profoundly affecting the course of the 20th century.

Achievements

as per 1912

By 1912, Leon Trotsky had already established himself as a leading revolutionary intellect and organiser, even though the full storm of 1917 was still ahead. One of his signal achievements so far was his role in the 1905 Revolution, where as chairman of the St. Petersburg Soviet he led what was effectively a parallel government of workers for 50 days. During that time, Trotsky honed the tactics of mass strikes and demonstrated extraordinary ability to articulate the grievances and aspirations of the working class. Though the uprising was crushed, his performance made him famous throughout socialist circles. In exile afterwards, Trotsky achieved a sort of reconciliation between rival Marxist factions: in 1910–1912, he convened talks in Vienna aiming to heal the split between Lenin’s Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks. While ultimately unsuccessful (Lenin remained wary of him), the attempt showed Trotsky’s clout and diplomatic skills among émigré revolutionaries. Meanwhile, Trotsky was a prolific journalist and editor – by 1912 he had edited the influential Pravda newspaper (though he later ceded it to Bolshevik control), and was contributing incisive essays to socialist publications in several languages. This journalistic achievement kept radical ideas alive and connected across borders. Additionally, in 1912 Trotsky published Results and Prospects, a work expanding on his theory of permanent revolution – a notable theoretical achievement that set him apart from other Marxists. And practically, while in Vienna, Trotsky founded and ran “Pravda” (The Truth) for Russian workers, a feat of underground publishing that linked far-flung revolutionary cells. Thus by age 33, Trotsky’s résumé included leadership in Russia’s first revolution, seminal Marxist theory, and international socialist journalism – all achievements that made him one of the most respected (and feared by authorities) socialist leaders in the world, poised to play an outsized role when the next revolutionary opportunity arose.

Motive:

Background:

By 1912, Trotsky is a leading figure in the international socialist movement,

living in exile in Vienna and working tirelessly to unite the fractured Russian

revolutionary factions. He is deeply aware that the Tsarist secret police

(Okhrana) and other reactionary forces are constantly trying to infiltrate,

sabotage, and betray the revolutionary cause.

Baz Rutherford, presenting himself as a sympathetic British

journalist and supporter of the workers’ movement, manages to gain Trotsky’s

trust. Baz offers to help smuggle revolutionary pamphlets and funds into

Russia, and even volunteers to act as a courier between Trotsky’s group and

other socialist cells in Paris and Berlin.

However, Baz is in fact an opportunist and double agent,

selling information about Trotsky’s network to the Okhrana and to Western

intelligence agencies for personal gain. His betrayal leads to the arrest of

several of Trotsky’s comrades, the exposure of secret meeting places, and the

confiscation of vital printing equipment. Worse, Baz’s actions sow suspicion

and paranoia among the revolutionaries, undermining Trotsky’s efforts to build

unity and trust.

For Trotsky, Baz is not just a personal traitor—he is a

direct threat to the revolution itself. In Trotsky’s worldview, the struggle

for liberation is a matter of life and death, and those who betray the cause

for money or self-interest are enemies of the people. Trotsky is haunted by the

knowledge that Baz’s duplicity has cost lives and set back the movement at a

critical moment.

Summary:

Trotsky wants Baz dead because Baz’s treachery led to the arrest and suffering

of fellow revolutionaries, sabotaged the socialist cause, and endangered the

very possibility of revolution in Russia. For Trotsky, eliminating Baz is not

just personal vengeance—it is a revolutionary act of justice, a necessary step

to protect the movement from further betrayal.

In-character quote:

“He sold out the revolution for a handful of coins. For every comrade lost to

his treachery, he owes a debt in blood. The cause demands justice—and I am its

instrument.”

Chiang Kai-shek

Basic

Details

- Nationality: Chinese

- Profession: Revolutionary Military Officer (future Generalissimo)

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 25 years old (born 1887)

- Fictional Age in Story: ~25 (a young commander in 1912)

Core

Significance

Chiang Kai-shek is historically important as the leader of Nationalist China and a key figure in 20th-century Chinese history. He succeeded Sun Yat-sen as head of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) and led the Chinese government through tumultuous decades – unifying much of China in the 1920s, resisting Japanese invasion in World War II, and later heading the Chinese Nationalists on Taiwan after 1949. He is remembered for his role in the Northern Expedition unifying China, his steadfast (if sometimes autocratic) fight against both Japanese aggression and Chinese Communists, and for modernising parts of China’s bureaucracy and military. Though ultimately forced into exile in Taiwan, Chiang’s legacy looms large as a foundational figure in the shaping of modern China (and Taiwan), admired by some for his patriotism and criticised by others for authoritarian tendencies.

Early

Life and Background

Chiang was born into a salt-merchant family in Zhejiang province. Orphaned of his father early, he grew up disciplined and ambitious. In his teens he embraced Sun Yat-sen’s republican ideas and enrolled in a military academy in Japan, which exposed him to modern warfare and nationalist ideology. By the 1911 Xinhai Revolution, young Chiang returned to China to join the revolt against the Qing Dynasty. He distinguished himself in Shanghai during the uprising – at just 24, he helped capture an arsenal, displaying bravery and tactical skill. This brought him to the attention of Sun Yat-sen, who became Chiang’s political mentor. Chiang’s early influences were a mix of traditional Confucian values (respect for order and hierarchy) and the revolutionary fervour of a generation determined to strengthen China. In 1912, with the Qing empire collapsed, Chiang was a junior officer in the new republican army, sharpening his disdain for warlordism and his desire to see China united and strong under a central authority. These formative experiences – soldiering in the 1911 Revolution and observing the chaotic early republic – shaped Chiang into a no-nonsense military man who prized loyalty, discipline, and Chinese national unity above all.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

As the decades unfolded, Chiang Kai-shek’s legacy became that of a champion of Chinese nationalism and a central, if controversial, figure in the struggle for China’s destiny. He famously led the Northern Expedition (1926–1928), smashing warlord fiefdoms and nominally unifying China under the Nationalist government. During World War II, Generalissimo Chiang was one of the Allied leaders, his armies tying down vast Japanese forces in China (though at appalling cost to the Chinese people). Internationally, he was seen as a key Allied partner in defeating fascism. Domestically, however, his regime struggled with corruption and never fully won over the populace, especially in the face of the Communist challenge. In 1949, after years of civil war, Chiang’s Nationalists were defeated by Mao Zedong’s Communists, and Chiang retreated to Taiwan. There, he established an authoritarian government-in-exile that transformed Taiwan with land reforms and economic growth, laying the groundwork for the island’s later prosperity. Today, Chiang’s historical impact is viewed in dual light: on one hand, he is credited as a staunch anti-Communist who kept alive an alternative Chinese state (Taiwan) and as a nationalist who strove to modernise China’s military; on the other, he is critiqued for authoritarian rule and strategic missteps that led to the Communist victory. Nevertheless, Chiang’s imprint is indelible – cities, highways, and institutions in Taiwan bear his name, and his role in World War II secured China’s position among the victors. In sum, Chiang Kai-shek shaped the course of Chinese history by both unifying and then losing mainland China, and by preserving Chinese national identity on Taiwan, making him a pivotal figure of the 20th century.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, Chiang Kai-shek was still a rising young officer, but he had already made notable contributions to the Republican cause. He had fought in the revolutionary battles that toppled the Qing Dynasty in 1911 – distinguishing himself in Shanghai when his unit seized the city’s weapon stockpile from imperial forces. This bold action not only supplied the revolutionaries with arms but also proved Chiang’s courage and leadership under fire. In 1912, with the new Republic of China established, Chiang became a founding member of the Kuomintang (KMT) and was appointed commandant of a prestigious cadet corps in his native Zhejiang: an early achievement that gave him experience in training troops. He also served as an aide to Chen Qimei, the military governor of Shanghai, wherein he helped organise the city’s defence and police in the chaotic first year of the republic. Though junior in rank, Chiang’s organisational flair and strict discipline were evident – he created drill manuals for the provincial army and enforced anti-warlord cohesion among the Zhejiang units. These accomplishments – from battlefield exploits to honing military administration – marked Chiang by 1912 as a promising young man to watch in Sun Yat-sen’s revolutionary circle. Indeed, Sun took the extraordinary step of sending Chiang on a fact-finding trip to Japan in late 1912 to study modern military techniques – a sign of the trust already placed in him. All told, by age 25, Chiang had transitioned from academy cadet to a battle-tested captain of the revolution, cementing his place among the next generation of Chinese nationalist leaders.

Subhas Chandra Bose

Basic

Details

- Nationality: Indian

- Profession/Role: Nationalist Leader, Revolutionary

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 15 years old (born 1897)

- Age in Story: ~25 (portrayed older for the 1912 event)

Core

Significance

Subhas Chandra Bose is remembered as one of India’s most impassioned freedom fighters, a radical leader who sought to overthrow British colonial rule by force. Reverently called “Netaji” (Hindi for “Respected Leader”), Bose broke away from the pacifist path of Gandhi’s Indian National Congress and instead formed the Indian National Army (INA) during World War II to fight the British alongside the Axis powers. His rallying cry “Jai Hind” (“Hail India”) and vision of unfettered Indian sovereignty made him a heroic figure to many Indians. Although the INA’s efforts did not directly win independence, Bose’s actions galvanised Indian nationalism and weakened British resolve to hold India. To this day, he symbolizes militant patriotism and the willingness to make ultimate sacrifices for one’s country’s freedom.

Early

Life and Background

Subhas Bose was born on 23 January 1897 in Cuttack, Orissa, into a large, well-to-do Bengali family. He was a brilliant student at the Protestant European School in Cuttack and later at Presidency College in Calcutta. Bose’s upbringing instilled in him both traditional Indian values and a British-style education, giving him fluency in English and an exposure to Western political thought. Even as a teenager, he was profoundly influenced by the Indian independence movement, absorbing the writings of Swami Vivekananda and hearing of nationalist icons like Bal Gangadhar Tilak. In college, Bose demonstrated a fiery temperament against racial injustice: in 1916, he famously assaulted a British professor who had demeaned Indian students, an incident that got Bose expelled from Presidency College. This youthful act of defiance was a harbinger of the bold approach he would later take in challenging the Raj. Despite the setback, Bose completed his education, ranking high in the Indian Civil Service entrance exam in England—only to resign in April 1921 before joining the colonial bureaucracy, firmly convinced that his destiny lay in serving India’s liberation, not the British administration.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Subhas Chandra Bose’s legacy in India is complex but deeply influential. He is hailed by many as the first leader who attempted to organise an armed insurrection against British rule on a truly national scale. The existence of his Indian National Army in the 1940s – composed of Indian POWs and expatriates in Southeast Asia – demonstrated that Indian soldiers could be united under a national flag rather than the Union Jack. This spectacle of Bose marching troops under the tricolour Indian flag and his proclamation of a Provisional Government of Free India in 1943 sent electrifying hope through the subcontinent. After the war, although Britain dismissed the INA as a failed collaborationist force, the Red Fort trials (where INA officers were court-martialled in 1945) ignited massive public support across India’s religious and regional divides. Many historians argue that this shift in Indian loyalty and unity spurred by Bose’s movement hastened the British decision to quit India in 1947. Bose’s slogan “Give me blood and I promise you freedom!” remains iconic, reflecting his belief in sacrifice for liberty. While he courted controversy by allying with fascist regimes (a decision born from “enemy of my enemy” logic), Bose is widely respected in India as a patriot whose extreme choices were driven by unflinching love for his motherland. His legacy also influenced post-colonial Indian defence strategy and inspired later nationalist and even separatist movements in different countries who saw Bose as proof that indigenous forces could challenge imperial might. In present-day India, Netaji’s statues, stadiums, and holidays commemorate him, and debates about his mysterious death (in a 1945 plane crash, though some believe he survived) continue to intrigue the public. Above all, Bose’s historical impact lies in showing that the quest for independence could go beyond petitions and peaceful protests – it could, if necessary, take up arms and still galvanize a nation’s spirit.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, Subhas Bose was still a young man in the throes of education, yet he had already shown signs of the leadership and rebellious zeal that would define him. In 1912 he was studying at Scottish Church College in Calcutta, where he excelled academically, topping his class in philosophy. More tellingly, he had become involved in student discussions about independence and was drawn to the teachings of radical nationalists like Aurobindo Ghosh. That year, Bose volunteered with the Bengal Swadeshi movement, helping promote indigenous products and boycotts of British goods – a cause that took him to villages to raise awareness, honing his skills as a persuasive orator in his late teens. He also organized classmates in acts of civil disobedience, such as protests against the British partition of Bengal, demonstrating a natural ability to inspire peers. While he held no official position yet, Bose’s intellectual brilliance had earned him a mentorship under Chittaranjan Das (a prominent nationalist lawyer in Bengal) who recognized the youngster’s potential. In sum, by 1912 Subhas Bose’s achievements included academic distinction, burgeoning involvement in nationalist circles, and a reputation as a strong-willed young patriot unafraid to speak out – qualities that were the seeds of his future prominence.

Haile Selassie

Basic

Details

- Nationality: Ethiopian

- Profession: Prince (Regent), later Emperor of Ethiopia

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 20 years old (born 1892)

- Age in Story: ~20 (portrayed at actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen) is historically celebrated as the Emperor of Ethiopia (1930–1974) who led one of Africa’s only long-independent nations through tumultuous 20th-century events. Internationally, he became the face of African resistance to colonial aggression when he appealed to the League of Nations in 1936 after Fascist Italy’s brutal invasion – an iconic moment that exposed the League’s weakness and rallied global sympathy. Post-WWII, Selassie was a key figure in African decolonisation and unity, helping establish the Organization of African Unity (precursor to the African Union) in 1963. He is revered in Rastafarianism as a messianic figure (“Lion of Judah”), giving him a spiritual significance beyond politics. In essence, Haile Selassie’s importance lies in being a symbol of African sovereignty and reform, an international statesman who tried to modernise Ethiopia while fiercely guarding its ancient independence, and a global voice against fascism and racism.

Early

Life and Background

Born as Lij Tafari Makonnen in 1892 to a noble Ethiopian family (his father was governor of Harar and cousin to Emperor Menelik II), he was groomed from childhood for leadership. Exceptionally bright and diligent, young Tafari stood out at Menelik’s court, mastering Amharic, French, and clerical skills. In 1911, he married Menelik’s daughter, elevating his royal status. By 1912 – with Emperor Menelik II deceased (1904) and his successor Lij Iyasu unstable – Tafari Makonnen, at just 20, had been appointed Dejazmach (commander) of the crucial province of Sidamo. In that role he showed administrative acumen: introducing modern schools (one of which he funded himself), inviting European advisers to train his army, and diplomatically expanding his influence among regional princes. Also in 1912, he gained the title of Ras (equivalent to Duke) and had become a confidant of Empress Zewditu (Menelik’s daughter who would soon take the throne). Ras Tafari was positioning himself as a progressive voice at court, cautiously advocating for technologies like the telegraph and railway to connect Ethiopia internally and with the outside world. Surrounded by conservative nobles, he trod carefully, but by 1912 he was clearly the rising star of Ethiopia: he had successfully quelled a minor rebellion in Sidamo without excessive bloodshed – a feat that enhanced his reputation for wisdom and mercy. Thus, at 20, while not yet emperor, Tafari Makonnen had earned respect as a capable regional governor, a moderniser with panache, and a princely diplomat who commanded loyalty and intrigue in the power struggles of the Ethiopian Empire’s twilight traditional era.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Haile Selassie’s legacy looms large over Ethiopia and Africa. He presided over the modernization of Ethiopia – introducing the country’s first constitution in 1931, promoting education (founding the University College of Addis Ababa), and slowly centralising power from feudal lords to the imperial government. Though his pace of reform was sometimes criticized as too slow, he took a fiercely independent, ancient kingdom and navigated it through the currents of the 20th century, keeping Ethiopia sovereign when virtually all of Africa fell under colonial rule. Internationally, his impassioned plea to the League of Nations (“It is us today, it will be you tomorrow”) after Italy’s invasion was a prophetic denunciation of appeasement, and though the League failed Ethiopia, Selassie’s dignified fight made him an anti-fascist icon. After WWII, he regained his throne and became an active global statesman – he contributed Ethiopian troops to the Korean War under the UN flag (cementing him as a partner in collective security), and he was among the first heads of state to recognize newly independent African countries, championing Pan-Africanism. In 1963, heads of African states converged in Addis Ababa largely due to Selassie’s prestige, and there they formed the OAU with him as a founding figure. This earned him the epithet “Father of African Unity.” However, his legacy is not without complexity: by the 1970s, critics pointed to his autocratic style and failure to fundamentally uplift the rural poor; a famine in 1973 and discontent led to his overthrow in 1974 by communist Derg officers. Yet even in dethronement, his mystique endured, especially among Rastafarians who had since the 1930s venerated him as the returned messiah (based on his titles like “Conquering Lion of Judah”). Today, Haile Selassie is remembered as a towering figure of African independence, a reformer-king who tried to balance tradition with progress, and a symbol (even deified in some culture) of black pride and resilience. Ethiopia’s avoidance of long-term colonization stands partly to his credit, and his words and visage remain emblematic in Pan-African forums and reggae music alike.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, young Ras Tafari (Haile Selassie’s title at the time) had already distinguished himself in Ethiopia’s fractious political arena. That year was pivotal: Emperor Menelik II had died a few years earlier and Menelik’s grandson Lij Iyasu was supposed to succeed him, but Iyasu’s erratic rule was alienating the nobility. Tafari Makonnen, through careful networking and sagacious administration, achieved de facto leadership among the progressive faction at court. In terms of formal posts, in 1912 he was appointed as Governor (Ras) of Harar, one of the empire’s most important provinces and a center of commerce and Islamic culture. Taking charge in Harar (the position held formerly by his father), Tafari effectively pacified the region and implemented new policies: he expanded the city’s road networks and encouraged foreign traders (French and Indians) to settle, boosting the local economy. This appointment at just 20 was a huge vote of confidence from the regency council overseeing the empire. Also in 1912, Ras Tafari negotiated a diplomatically delicate marriage alliance: though already married, he arranged his sister’s marriage into a rival noble house, which helped neutralize a potential threat to Empress Zewditu’s succession. Thus, he proved his skill in diplomacy and alliance-building. Within the imperial court, Tafari introduced an innovative idea: sending young Ethiopians abroad for education. In 1912 he secured permission (and funding) to send a handful of students to Europe – a small step, but one that planted seeds for a modern educated class which he would later rely on. Recognition of his growing influence came in late 1912 when Empress Zewditu (who took the throne that year) named him Balemulu Silt’an (Head Regent and heir-presumptive) – effectively making him next in line to the throne given Lij Iyasu’s deposition. This was an extraordinary achievement for someone of his age, marking him as the highest intellectual and political authority behind the empress. Such elevation was due to his proven record: he had kept peace in his provinces, fostered ties with foreign envoys (by 1912, diplomats from Britain and France were corresponding directly with Ras Tafari on regional matters), and shown personal bravery in quelling a tribal unrest on the Somaliland frontier that year. In summary, by 1912 Haile Selassie had achieved unprecedented power for a man of 20 in Ethiopia, becoming the empire’s key modernizer, a trusted regional governor, and the clear successor to the throne – all through shrewd diplomacy, effective governance, and a forward-looking vision that was already bearing fruit.

Fritz Joubert Duquesne

Basic

Details

- Nationality: South African (of Boer ancestry)

- Profession: Soldier, Spy, Adventurer

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 35 years old (born 1877)

- Age in Story: ~35 (portrayed at or near his actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Fritz Joubert Duquesne is historically infamous as a master spy and saboteur who worked against the British Empire during the early 20th century. A veteran of the Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902) on the Boer side, he later became a German spy in both World Wars, earning nicknames like “The Black Panther” for his stealth. He is perhaps best known for leading the Duquesne Spy Ring in the United States (uncovered in 1941, the largest espionage case in US history at the time). Duquesne claimed to have committed daring acts, including the alleged assassination of Lord Kitchener by sinking his ship in 1916. Though some of his tales were embellished, there’s no doubt he was a consummate infiltrator and escape artist, whose life reads like a pulp thriller. He symbolizes the lengths to which a bitter adversary of British colonialism would go – embodying the role of the relentless revenge-driven spy. In short, Duquesne’s importance lies in being one of the most colorful and effective espionage agents of his era, operating across continents and leaving a legacy of intrigue and folklore behind.

Early

Life and Background

Born in 1877 in East Cape Colony (in what is now South Africa), Fritz Duquesne grew up amid colonial conflicts. His family were well-off Afrikaner farmers. When the British scorched earth and put his mother and sister in a concentration camp during the Boer War, young Fritz’s life purpose crystallised into hatred of the British. He fought tenaciously as a Boer commando, mastering guerrilla tactics. Captured by the British, he used charm and cunning to escape prison – a pattern that would define his life. Fluent in several languages and able to adopt multiple identities, Duquesne drifted after the war, doing everything from big-game hunting in Africa to journalism in New York. By 1912, he had already been involved in a scandalous insurance fraud: he posed as a game ranger and burned down a ship (the Tintagel Castle) for an insurance payout, demonstrating his penchant for sabotage. Settling in the US, he ingratiated himself with high society (at one point working as a press agent). All of this was backdrop to his true calling: espionage. By 1912, though not formally employed as a spy yet, he was in contact with German agents, offering his services in anticipation of the next showdown with Britain. Duquesne’s early experiences – witnessing British brutality, perfecting the art of deception for survival, and cultivating an undying thirst for retribution – forged him into a man who lived by wits and vengeful zeal. He honed skills in disguise, explosives, and manipulation. In essence, by the eve of World War I, Duquesne was a free agent saboteur armed with personal motive and talent, ready to be hired by anyone against the British Empire.

Legacy

and Historical Impact

Duquesne’s legacy is shrouded in espionage lore. He inflicted real damage as a German spy in World War I (credited with acts of sabotage in Africa and Europe) and later became the ringleader of a major Nazi spy network in the US during World War II. That 1941 FBI bust – the Duquesne Spy Ring of 33 agents – was a huge victory for American counterintelligence and put Duquesne behind bars for good, marking the end of his long cat-and-mouse game. Culturally, Duquesne’s life story influenced fictional characters – he’s like a prototype of the maverick secret agent, albeit on the wrong side. In South African memory, he remained a controversial figure: some Boers regarded him as a folk hero who avenged their suffering, while others felt his later alignment with Germany tainted his patriotism. Globally, his impact is a reminder that the legacies of colonial wars bled into the world wars; he personally tied the Boer resistance to later conflicts. Though not as historically pivotal as statesmen or generals, Duquesne’s century-spanning spy career underscores the evolving nature of espionage – from blowing up trains on horseback to sending encrypted radio messages from Manhattan high-rises. The sheer audacity of his operations, if sometimes exaggerated by Duquesne himself, left behind a train of sensational headlines and FBI case studies. In the end, his greatest contribution to history may be as a case study in perseverance in covert war – he literally spent decades fighting an enemy by any means. The fact that his exploits fill archives and inspired spy novelists is testament to a legacy of intrigue that outlived the man: Duquesne exemplified the deadly spy-for-hire that thrived in the chaotic first half of the 20th century.

Achievements

as per 1912

By the end of 1912, Fritz Duquesne had already achieved the stuff of adventure novels. Most notably, he had survived the Boer War, during which he led guerrilla raids so effective a bounty was put on his head. Not only did he evade capture for long, when the British finally caught him they sent him to a POW camp – from which he escaped (reportedly by feigning paralysis and slipping away once moved to a civilian hospital). That alone made him a minor legend among former Boer comrades. Post-war, Duquesne carried out a personal mission around 1909–1910: infiltrating British circles by posing as a Brazilian cattle rancher, he orchestrated the destruction of the British ship Tintagel Castle by arson at sea (to avenge, he claimed, British atrocities and also pocket insurance money). By 1912, he had dodged prosecution for that crime, leaving investigators baffled – an achievement in elusiveness. In New York, he had established himself under alias as a respected war correspondent and lecturer, giving talks about his Boer commando days to rapt audiences who had no idea he was scheming against the British behind his suave storytelling. He ingratiated himself with wealthy benefactors, even reportedly charming his way into dinners (not unlike the 1912 event at hand). Thus, by this year, Duquesne’s achievements included a trail of successful conquests via deceit: he had fooled countless people, used false identities profitably (including drawing a US government salary as a “scout” at one point), and was gathering intelligence on British shipping and defenses under the noses of those who thought him just a charismatic foreign gentleman. While he did not yet have the infamy of later years, those in certain circles whispered about the “Boer super-spy” – a harbinger of the extensive espionage career to come. In short, as of 1912, Duquesne had proven uncommonly adept at guerilla warfare, escape, impersonation, and sabotage, setting the stage for his World War roles.

Winston Churchill

Basic

Details

- Nationality: British

- Profession: Politician (First Lord of the Admiralty)

- Gender: Male

- Age on 25 December 1912 (Real Life): 38 years old (born 1874)

- Age in Story: 38 (portrayed at his actual age in 1912)

Core

Significance

Winston Churchill is historically renowned as a towering British statesman and wartime leader. He served twice as UK Prime Minister (including during World War II) and is celebrated for his rousing oratory, steadfast refusal to bow to Nazism, and guiding Britain (and the Allies) to victory in WWII. Earlier, he had a pivotal role in World War I’s military strategy and later helped shape the post-war world order (he famously warned of the Iron Curtain after WWII). Churchill’s legacy endures as a symbol of courageous leadership, with speeches like “We shall fight on the beaches” embodying defiance. In short, he is remembered as one of the 20th century’s most influential leaders, a master orator, and a strategist whose career spanned the zenith of the British Empire through its challenges of global war.

Early

Life and Background